Thanksgiving is my favorite holiday and I miss it. Here in France, lots of Americans celebrate this day by preparing a Thanksgiving feast with all the trimmings. But having partaken of these meals, I can say it’s not the same. Turkey and stuffing somehow taste better when I share them with my family in the United States.

This year, on Thanksgiving Day, France was in lockdown. Since late October, the nation has once again been placed under quarantine. In terms of per capita deaths, the figures in France are close to those of the US. Hospitals cannot keep up with the arrival of new patients and testing capacities remain inadequate. In public we wear masks and the government asks citizens to limit private gatherings to no more than six persons.

A week before Thanksgiving Day, the C.D.C. encouraged Americans to do the same: stay home and celebrate with the immediate family instead of taking off during what traditionally is the most busy travel time of the year. Somehow it doesn’t feel like Thanksgiving, at least not the way it used to be.

This year on Thanksgiving Day, I sat home alone. Except for the allotted hour of outdoor exercise, in my case, a walk through forest and fields, I spent the day inside, under quarantine. I ate pasta with pesto sauce and a spinach salad, probably the greenest Thanksgiving dinner of my life, and I gave thanks. I am well, all my basic needs are satisfied, and I love and am loved. This is what is essential in life.

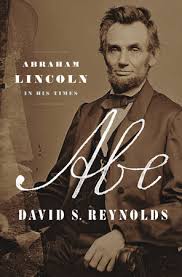

As always, in lockdown or not, I spend a lot of time reading. This month, two books have stood out. One is a biography of Abraham Lincoln. Entitled very simply “Abe,” it is written by David Reynolds, who has placed Lincoln within the cultural context of his times. I am learning that our 16th president was quite a roughneck in his youth, brawling to prove his strength, but rejecting eye-gouging, a practice popular among young men on the frontier.

In the 1830’s, the state of Illinois, where Lincoln first held elected office, was where that frontier began and settlers were not afraid of taking the law into their own hands. If you disagreed with your neighbor, you went after him with a horsewhip. If a newspaper editor expressed ideas you didn’t like, you simply shot him dead.

In November 1837, the year Lincoln was elected to the Illinois legislature, this is exactly what happened to Elijah Parish Lovejoy, an abolitionist newspaper editor in Alton, Illinois. He was attacked and killed while defending his printing presses from an angry pro-slavery mob. In 1838, in a state where anti-abolitionists were a majority, Lincoln spoke out against what he called the “mobocratic spirit” behind the attack and cautioned that such incidents threatened to destroy American democracy.

A passionate and emotional man, Lincoln understood the importance of controlling emotions and bringing about change through debate, persuasion, and the law. Growing up on the frontier, he feared both anarchy and tyranny and was not afraid of knocking fledgling tyrants down a notch. He understood all too well that a tyrant with no respect for the American system could possibly take control.

Above all, he placed his respect in the law, for even a bad law can be changed. “Let reverence for the laws, Lincoln wrote, be breathed by every American—let it be the political religion. If we fail, we must die by suicide.”

Quarantined with Abraham Lincoln, I am in good company.

In my French home, I also have a piece of Pottsville, a book about the anthracite region. I am reading “River of Gifts” written by Sherrill Silberling and illustrated by JoAnne Doyle.

In a collection of short stories, Ms. Silberling has turned her mother’s memories of Schuylkill County in the 1920’s into stories told simply and lovingly, perfect holiday reading. These are tales of a happy childhood in a loving family, back in the days when food, shelter, and love were enough. The final story in the collection, “The Gift,” is a tribute to a mother who, by instilling trust, gave the gift of life-long confidence to her child. Next to love, is there a gift more precious?

So far, my time in quarantine has been well spent in the nurturing company of good books, but don’t worry, I do other things besides read. Occasionally I watch a good movie on TV. A few night ago, I watched an excellent made-for-TV movie called “La maladroite,” The Awkward Girl,” directed by Eleanor Faucher. Based on true events, it tells the story of a young girl whose parents first destroy their daughter’s confidence and then take her life.

According to the latest official statistics, which concern 2018, 80 children a year in France lose their lives because of family violence. That comes to one child every five days. In many cases, such as that of Marina Sabatier, whose child-abuse death in 2009 inspired the film, teachers and social workers are aware of the abuse, doctors intervene, yet it seems almost impossible to remove the child from the home. Often, the abused child loves and protects the parents because abuse is all she knows.

To appreciate “La maladroite,” a viewer does not need to understand French. Elsa Hyvaert, the very young actress who plays the role of the abused child, speaks a poignant language beyond words. I encourage readers to watch this film and here is a link where it can be streamed: https://www.france.tv/series-et-fictions/telefilms/1103191-la-maladroite.html

A 2019 report found that child-abuse related deaths are on the rise in Pennsylvania. In Annville, in neighboring Lebanon County, a 12-year-old boy was found dead of starvation and abuse in September 2020. The father and his fiancée have been charged with homicide. The Lebanon County DA Pier Hess Graf stated that this boy “never knew the unconditional love from a family.”

Covid and political turmoil seem to reign everywhere in the world today, yet a child who is loved, anyone who is loved, has much to be thankful for. This, for me, is what it means to be “pro-life,” making sure a child’s emotional and physical needs are met from birth onwards. Though my wish may be little more than an ideal, this is what I hope for every child.