Published in The Republican Herald, January 27, 2013

A current art exhibit in Paris, a “blockbuster show,” as it has been called in the French press, has carried me back to Schuylkill County, filling me with strong nostalgia for home. The exhibit, which will end on February 3rd, is devoted to the work of Edward Hopper (1882-1967). The French have proclaimed him the greatest American painter of the 20th century.

In the Grand Palais, an enormous exhibition hall between the Champs Elysées and the Seine, 128 of Hopper’s works have been brought together from all over the United States, being exhibited together for the first time ever. To see all these paintings, engravings and watercolors on American soil, it would be necessary to travel from sea to shining sea, from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico, visiting museums and art galleries from coast to coast.

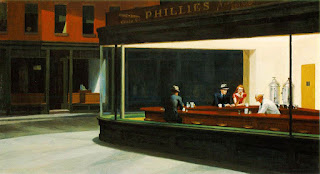

In Paris, under one roof, we can see them all—if we’re ready to stand in line for two or three hours, or, once inside, stand on tiptoe to catch a glance of Hopper’s most famous painting, “Nighthawks,” which measures a little over 50 inches in length but is only 22 inches high. Hard work, waiting and then battling the crowds, but the French are up to the challenge. Hopper has been dubbed “an American for the French,” presenting them with images that correspond to their idea of the United States, a nation of loners lost on a vast continent.

Their vision, however, is not mine. For me, Hopper is inseparable from my memories of growing up in Schuylkill County, of how it used to be and still is.

I first discovered Hopper’s work when I was in high school, thanks to my art teacher, Mr. Robert Koslosky, fondly remembered by anyone who had the good fortune to study with him. Each year, with members of the sketch club, he organized a trip to New York City and there, at the Whitney Museum of American Art, I first met Hopper, though I had the feeling I already knew him, his paintings immediately haunting me with a sense of “déjà vu.”

I recognized the streets of redbrick buildings rising no more than two storeys high, the railroad platforms (in those days there was still daily train service between Pottsville and Philadelphia), the Victorian homes, the vacant lots overgrown with weeds. As a child, I used to play at one on Greenwood Hill, next to the fire company, a gravel and coal dirt field later replaced by a “real” playground.

After that trip, after that encounter with an artist I knew would count for me, I went to the Pottsville Library and looked for more of Hopper’s paintings (today, if you scroll down the Wikipedia site in French, you’ll find a long list of links to Hopper’s works, more than on the English-language page: http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Hopper). There, what I saw in art books reconfirmed my initial sense of “déjà vu.” Discovering other paintings, I discovered places I already knew.

His 1927 painting of a drug store reminded me of Cable’s Pharmacy, once located at Second and Market Streets. In the display window, dominating the bottles of perfume and boxes of chocolates, were two suspended glass globes, each filled with colored water, catching and reflecting light. They were natural beacons, which is how they were used before the invention of electricity.

Hopper painted many streets and building façades that would look familiar to residents of Schuylkill County, including, in 1947, a street in a Pennsylvania coal town. He is also well known as a painter of interior scenes associated with transience: hotel rooms, motels or restaurants. Looking at some of the restaurant scenes, painted in muted tones of gold and burnished brown, I’m reminded of my all-time favorite restaurant in Schuylkill County, once located in the building home to the Brass Tap Tavern today.

I’m wondering how many readers, like me, often crossed the threshold of Joyce’s, turning into Logan’s Alley and pushing open the door of the “Ladies’ Entrance.” Hard drinkers entered on East Norwegian Street to gain direct access to the bar, but those of us who wanted to sit down in a booth for a meal entered on the side. Once inside, we were greeted by chef Joe Talpash, who was on a first-name basis with everyone.

“Got some fresh blue fish for you, Mary,” he often announced to my mother as we slid into a wraparound booth, and following Joe’s suggestion, that’s what she ordered, a sizzling filet of fish, served on the plate on which it was broiled, along with julienne fries, thin and crisp. Joyce’s Restaurant also reminds me of my father, Lewis, who died in 1968. He often took us to “Joe’s,” as we called it, for steamed clams, oysters or lobster tail. Thanks to Joe Talpash, my family became lovers of seafood and shellfish, what I’d call “coal region food.” When we wanted crab cakes, however, we deserted Joe and headed to Melnic’s in Saint Clair.

Looking at Hopper’s black and white engravings, I have a different kind of memory. I’m reminded of Schuylkill County artist Nick Bervinchak, whom I had the honor to meet before he died in 1978. Though he is best known for his mining scenes, I remember in particular one of his etchings of a ticket counter at the Reading Terminal in Philadelphia. The atmosphere and the angle of the scene (we see a heavyset woman from behind, leaning on the counter, waiting to purchase a ticket to the shore) could have very well been chosen by Hopper himself.

I am a child of the second half of the 20th century. Of course, I am also my parents’ child and Hopper’s work has the power to intimately connect me to their world, to that first half of the century when they were growing up and, in my father’s case, going to war. Though limited to an instant frozen in time, Hopper’s paintings tell stories, suggesting past and future, speaking to us about his world, but also about our own.

I don’t think Hopper ever visited Schuylkill County, but to those of us born or living here, he has many stories to tell. His work, viewed in Paris, poignantly carried me home.

dimanche 27 janvier 2013

Inscription à :

Articles (Atom)