dimanche 25 janvier 2015

“Timbuktu” and terrorism, at home and far away

At the beginning of January, I joined Sarah, a very old friend of mine, for a Sunday afternoon at the movies. I’ll never forget the first time we met 23 years ago. In January 1992, Sarah appeared in a sixth-grade English class I taught in a private school in Paris. This new student had big, thoughtful eyes and looked wise beyond her years.

Sarah is from Bangladesh and in January 1992, her father became his country’s ambassador to France. Before, he had been serving in Kuwait, but at the time of the first Gulf War, he and his family had to flee across the desert to safety in Jordan. Sarah spent her early years in Poland when that country was under martial law, before the victory of Solidarity. By the time we met, Sarah, 11 years old, had quite an experience of the world.

Today Sarah lives in Bangladesh and teaches at Asian University for Women. She has a PhD in Economics from Harvard, but rather than turn her talents to international finance, she has committed herself to helping other women in her part of the world.

In 2015, Sarah has the same beautiful, thoughtful eyes and she remains wise beyond her years. Whenever she visits Paris, we meet and I always discover something new thanks to her.

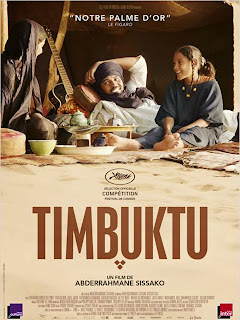

This time, she suggested we see the film “Timbuktu,” nominated to compete in the 2015 Oscars for the best foreign language film and to be released in the US on January 28th. I hope it will come to a theater near you but if it doesn’t, I encourage readers to note this title and rent it if you can.

When I was a child, I dreamed of wandering “all the way to Timbuktu” without the slightest idea of where such a place could be. Two years ago, war in Mali brought that city into my living room through the evening news. In January 2013 France launched “Operation Serval,” sending troops into northern Mali to support that country’s army fighting an invasion of Islamist militias.

The movie “Timbuktu,” directed by the Mauritanian Abderrahmane Sissako, takes us back to 2012-13, the time of the Islamist occupation of that legendary city, home to a collection of ancient manuscripts and once surrounded by hundreds of Sufi shrines, destroyed by the invaders. The first image of the film shows a jihadist at target practice, blowing traditional African sculptures to bits.

The fighters themselves are a motley crew, some young, some old, some experienced soldiers, others lost young men who just want to go back home. They speak a jumble of languages and have as much trouble understanding each other as they do the racially and culturally diverse inhabitants of Timbuktu, who do not give in easily to the harsh laws these half-baked followers of radical Islam seek to impose.

They outlaw music but a young fighter from the Libyan desert falls under the spell of a voice singing in the night. They’re praising Allah, he tells his superior, incapable of understanding the words. Another night, the singers will not be so lucky and a young woman receives a public flogging the next day.

They outlaw soccer, the national sport of Mali, yet to fight boredom, jihadists from France pass their time reliving the careers of their favorite players.

Another French jihadist, a man in his thirties, finally learns to drive (readers may remember what I went through to get a driver’s license in France). After several attempts, he finally, joyfully, gets the knack of driving his chauffeur’s pickup around in circles in the desert sands.

In “Timbuktu,” there are no monsters, only men and women, victims of themselves, of each other, and of a system, the morbid interpretation of the Koran by a group of angry, lost, frustrated men, too fearful of each other and of their God to think for themselves.

“Timbuktu” is also the story of the deep love between a father and his daughter. They are nomadic Tuaregs, living in tents, herding their cattle in the Sahel. When a stray cow destroys the nets of a sedentary fisherman, conflict erupts and with it come tragedy and the deadly justice of a misguided band of Islamists. (To see a trailer of the film: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CspcDYQ-SiY)

A few days after I saw “Timbuktu,” Paris became the target of homegrown jihadists in a series of terrorist attacks that made worldwide news. On January 7th, eight journalists were killed at the headquarters of Charlie Hebdo, a weekly newspaper of satire and commentary known for its irreverent tone. It was its caricatures of the Prophet Mohammed that incited the Kouachi brothers to take the journalists’ lives. Two policemen and a maintenance worker were also killed that day.

On January 8th, a policewoman was killed by the Kouachis’ accomplice, Amedy Coulibaly.

On January 9th, he also killed four Jews while he held other customers and employees hostage in a kosher supermarket in Paris. On that day, when all three terrorists were killed by the police, I sat in front of my computer, watching blow-by-blow accounts of events in real time.

On January 11th, nearly four million French people marched through the streets in a show of national unity unlike any since the end of World War II.

On January 7th and 8th, at the same time French terrorists were murdering their victims in Paris, in northern Nigeria, members of Boko Haram, followers of a distorted brand of radical Islam, killed 2,000 while chasing 20,000 Nigerians from their homes. Sitting at my computer, I can look at images of that massacre in the comfort of my home.

Since Sarah has returned to Bangladesh, her country has been paralyzed by several hartals, massive strikes that in many cases turn violent. They are a part of her everyday life. Since childhood, events she has lived have made her aware of the tragic dimension of history, which may account for the wisdom in her eyes.

“Timbuktu” is about that tragic dimension and recent events in Paris have plunged us into its midst.

The 21st century was born under a double star: the worldwide explosion of the digital revolution; the explosion of international terrorism as well.

Yes, in the 21st century, we can have the world at our fingertips and terrorists at our front door. May we learn to be as wise as Sarah in confronting these difficult times.

Inscription à :

Articles (Atom)