dimanche 28 février 2016

Day tripping, the European Way

Sometimes I like to walk out my front door, into the street, and onto a train heading to an unknown destination. For someone like me, who does not own a car and cannot simply step on the gas and go, it’s a way to disconnect from daily life and immerse myself in the unknown.

To aid me in this venture, I can count on the SNCF, the Société nationale des chemins de fer français, the French national rail service. A pop-up appears on my computer screen, a flash sale demanding immediate attention: act now or pass up an incredible deal. I click, study a list of destinations, choose somewhere I’ve never been before, and buy.

Then, uplifted by my recent purchase, I return to the everyday drudgery of life in front of a screen, secure in the knowledge that not too far down the line new horizons are awaiting me.

Only a week ago, I got up early on a dark, damp Saturday morning and headed to Gare du Nord, the Parisian train station to all points north, the biggest train station in Europe and the second biggest in the world.

Inside the station, it was a very dreary scene. The homeless, slumped against walls and in dark corners, were just beginning to stir. The station’s mice were active too, exploring overflowing trash bags that clean-up crews had not yet removed. I joined a line of early-morning travelers about to undergo a security check. That done, I climbed on the train to Amsterdam.

But that’s not where I was going. Before reaching its final destination, it would make a stop in Antwerp, Belgium, and that’s where I was getting off.

My primary motivation was ignorance—my own—and a desire to put an end to it. I knew a little about Antwerp. I knew it was a place for buying and selling diamonds. I knew too that the painters Rubens and Van Dyck had lived there in the 17th century during the city’s golden age. I knew it was an important port and that the city’s inhabitants spoke Flemish. Upon arrival, I didn’t know much else.

Inside the station, a magnificent building inaugurated in 1905, I asked for a map and headed outside. In the distance towered a lacy steeple. It belonged to Our Lady of Antwerp, the city’s cathedral whose threshold I would cross later that day.

I chose the steeple as my guide toward the city center, but then I got sidetracked. That’s the kind of traveler I am, a bad companion for those who like to stick to a program of things to do and see. I like to wander, get lost, and end up where I had no intention of going in the first place.

That’s exactly what happened to me in Antwerp, a wrong turn that turned out to be a stroke of luck because I ended up on Vrijdagmarkt, Friday Market. At one corner of that square stands the Plantin-Moretus Museum, home to one of the world’s first industrial printing houses and two of the oldest printing presses in existence today. I said to myself, this is something to see, and went inside.

Until the late 19th century, the museum was also the family home and the workplace of descendents of Christophe Plantin, founder in 1576 of the Gulden Passer, The Golden Compass Printing House. Until its closing in 1876, when it was turned over to the Belgian state as a museum, the Plantin-Moretus family lived and worked in the large but compact building where, for their workers and themselves, nights were short and days were long.

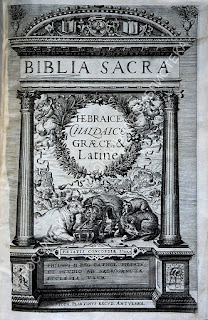

Once inside, visitors can pass directly from the family’s formal dining room whose walls are lined with family portraits, some painted by Rubens and Van Dyck, into the proof-reading rooms, offices, studies, a 17th century bookshop, and a print shop with seven presses that could produce 1,250 pages during a standard 14-hour workday. There are also ten tons of handmade moveable lead type, produced on the premises in the family’s foundry, and on one of the upper floors, the family library, which includes 638 rare manuscripts.

I’ll admit I’d never been to a place like this before. Though it calls itself a museum, the Plantin-Moretus Prentenkabinet feels a lot more like a workplace where everyone has just stepped out for lunch and at any moment, they’ll be back: Proofreaders seated at tables flooded with natural light, pouring over galleys straight off the press; compositors in the print shop setting the page, preparing it to be inked and “pressed” onto paper, very physical labor that requires flexibility and a good strong back.

In the study, its walls lined with fine Spanish leather, the 17th Humanist Justus Lipsius may be at work, in the space the family has provided for him to study, write and consult the thousands of works in the family library. His own complete works will be printed by Jan Moretus, the son-in-law of Christophe Plantin. And surely customers are standing at the counter in the bookshop, hoping to finger some of the leather-bound books produced at the Gulden Passer.

On this damp February day, there are few visitors and the museum is silent. Yet the air is alive with potential, as if the accumulation of centuries of love and care for the printed word could suddenly set the entire place ablaze with its former bustling activity.

Christophe Plantin had a motto: Labore et Constantia, by work and perseverance. For three centuries, for the Plantin-Moretus family, work and perseverance were enough. But in the mid-19th century, they refused to modernize: no rotary press, no photogravure, no linotype. The Gulden Passer remained frozen in time and progress passed it by.

In part, that is why the museum seems so alive today. Concentrating on their work, the printers missed out on a revolution. They may have loved their craft too well to care or to change.

After my visit to the Plantin-Moretus Museum, my time in Antwerp was almost up. I ran through the city, absorbing the sights at high speed, and didn’t even have time for some of those famous Belgian fries served with a dollop of mayonnaise.

Back on the train, I gazed at the night and felt a little less ignorant than at the start of my day. Then I dozed and dreamt, carried back to the time when the rush and clatter of the presses of The Pottsville Republican could still be heard on Mahantongo Street.

Inscription à :

Articles (Atom)