dimanche 23 février 2014

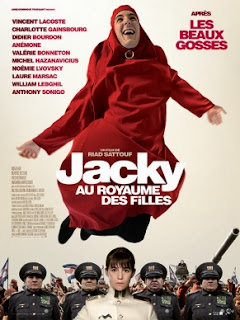

French “Cinderfella” gives a lesson in gender studies: Jacky au royaume des filles

Yesterday, I gave into a secret pleasure. On a blustery, brilliant Parisian afternoon, a true exception in a winter of relentless rain and gray, I slipped into the darkness of a movie theater to take in a matinee, a silly movie, a comedy, that turned out to be not so silly after all.

The title of the film, Jacky au royaume des filles, literally translates as “Jacky in the kingdom of girls,” but a much better title would be “Cinderfella,” because that’s who Jacky is, a masculine version of one of the most beloved fairy-tale princesses, Cinderella, who rose from raking ashes and scrubbing floors to sharing the throne with a prince whose ideal of the perfect bride was a woman with small feet.

Jacky lives in Bubunne, a kingdom where women rule and men obey, a desolate place with no gardens, parks or farms, no animals except for sacred ponies to whom boys pray, pleading to be turned into princes. While women patrol the streets, work in industry or govern—Bubunne is a military dictatorship, headed by a general about to step down in favor of her youngest daughter, “la Colonelle,” the men and boys stay home to cook and clean.

When they go out to shop or pray (sacred ponies don’t come inside), they always dress in “voileries,” a sack-like robe, something like a chador, that covers them from head to mid-calf, exposing their faces but covering the neck. Attached to the robe, just beneath the chin, hangs a silver ring. Upon marrying, wives can attach a leash to it to lead husbands through the streets.

The day the government announces “la Colonelle” will be giving a ball where she’ll choose her consort, the royal “couillon,” the number-one idiot of the land, all the boys go wild!

Of course, Jacky is already in love with “la Colonelle” (aren’t all the little boys?) and he dreams of going to the ball, but his mother dies and, taken in by a cruel aunt, with two husbands, by the way, he must stay home to cook and clean while his two cousins go instead.

By now, I’m sure readers have got the gist—in at least two ways. Jacky will marry “la Colonelle,” just like in the original. And this version of “Cinderella” is a fairy tale turned upside down, with all the roles reversed: women in charge, men scrubbing the floors; women wearing the pants, men covered by veils; women choosing (or, as is also the case in the film, harassing, even raping) and men patiently waiting to be the chosen ones.

Jacky au royaume des filles, directed by Riad Sattouf, is a good movie and it offers viewers a good time. In no way is it a feminist manifesto, but it just so happens that the film has been released at a moment when the word “gender,” as in gender studies, is making headlines in France.

In fact, on February 2nd, in Paris and Lyon, hundreds of thousands (according to organizers, far fewer, according to police) marched through the streets, waving pink and blue banners, protesting against a new program recently introduced in France’s public schools. Called the “ABCD of equality,” its goal is to undo stereotypes and promote equality between girls and boys from their earliest school days.

To give an example, in elementary schools, teachers work with images: a woman doing the shopping, a man repairing the kitchen sink, a couple cooking together, a little boy dressing up in a disguise. Students are asked to sort pictures according to whether they point to stereotypes or not. Disagreement can lead to heated discussion, even among the very young. When one boy suggests it’s OK for boys to cry, another protests: no! that means he’s a girl.

For this and for other ideas like it, such as using 19th-century paintings to discuss how women’s and children’s dress have changed or encouraging less violence on the playground, a part of France is up in arms—to the point that some parents, responding to rumors that the “ABCD of equality” is teaching their children to become homosexuals, intend to pull them out of school one day a month. Alerted by SMS’s that spread like wildfire, they are participating in a nation-wide boycott initiated by Farida Belghoul, a militant for family values, close to Dieudonné and Alain Soral, whom I wrote about last month.

Others are simply worried that schools are not doing their job, which is to teach children how to read, write and count. Still others feel public school is overstepping its bounds, making an unwarranted incursion into the private realm of family life.

In recent days, the whole affair reached proportions that forced the Minister of Education Vincent Peillon to reassure the nation that the “ABCD of equality” does not equal “gender studies,” a subject that will not be taught in French schools. In other words, though he is in favor of equality, far be it from him or the government to want to do away with one of France’s most beloved mottoes, “Vive la différence!”

But what’s wrong with gender studies, I’m tempted to ask. After all, its founder is the French feminist Simone de Beauvoir, who famously wrote, “One is not born a woman, but becomes one”—though you might say she was inspired by a man. In the 16th century, the Dutch humanist Erasmus wrote pretty much the same thing, claiming we become human, we are not born that way. In both examples, in the best cases, culture and society improve upon nature to make us who we are.

Which brings me back to Jacky. In Bubunne, boys cannot go to school because the ruling regime does not want them to learn to read. Inside or outside, they must be covered by a veil, hiding themselves from the roving gaze of…females. And men and boys do all the dirty work, preparing the daily “bouillie” or slops, recycled human waste, the main, the only, dish in Bubunne.

Veils, slops and ignorance imposed on men, silly stuff, isn’t it? It doesn’t seem very natural, does it? We all know men are strong and intelligent, the ones who rule the world! And women, well, aren’t they the ones who do the dirty work? Ask yourself, who cleans the toilet at your house?

Nature or culture, which one determines the tasks that men and women assume in society? Jacky has taught me more about gender studies than the current debate stirring up French society.

Inscription à :

Articles (Atom)